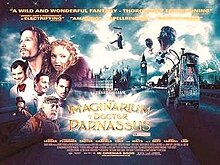

I finally saw this cult classic of Terry Gilliam and Heath Ledger's final half-performance. Like all my reviews, spoilers abound, so placing this below the cut.

Film blog originally about the themes behind Star Wars Episodes I, II, and III.

People who'd been following the progress of a third movie, sometimes referred to as God Particle or simply Untitled Cloverfield Project, might have sensed something was up when Paramount kept playing release-date musical chairs with it, moving it from February 2017 to October 2017, then February 2nd, 2018 ... then April 20th, 2018. And even these eagle-eyed watchers might have breezed past The Hollywood Reporter story in mid-January that hinted at Netflix being in talks to acquire the property, rumored to be in even rougher shape than previously imagined. At which point, the service thought: We can get this for a song. How do you save an unintentional suckfest? You turn it into a surprise event. That unveiling during the Super Bowl, part callback and part cryptic little sneak peek, is the sort of marketing coup that deserves an eternal slow-clap.

That's one way of looking at it, of course. Another way is that they've simply found a cutting-edge way to pull the oldest trick in the promotional book. When Ms. Knowles pioneered the surprise-album drop, she relied on old-school codes of omerta and a new technological infrastructure that suddenly allowed you to go from studio to iTunes in a click. If it's not the new norm, it was certainly a bold new business model, one applicable to the right combination of name recognition and supply/demand economics. Thanks to Netflix, which pays lip service to the theatrical-release model even as it seems hellbent on cutting it off at the knees, the film industry may now have its equivalent infrastructure for such moves as well. As an experiment in attracting attention, cost-benefit economics and dodging a flop-film bullet, this is a huge win.

For people who care about the quality of movies, including big blockbuster ones, and who will never get that 102 minutes back, however, this is not being Beyoncé-ed. It's the art of being P.T. Barnum-ed. At which point we can only look straight into the camera, fix the service with our best fretting Gugu Mbatha-Raw look, and solemnly intone:

"Whatever you're doing, Netflix: Stop."

A large shadow appears and then there's that mystifying roar. A child is found, and saved, and only kinda sorta mentioned again. Then, at the very end of all this, right before the credits, a giant monster appears, some sort of variation on the original Cloverfield kaiju. See? It really is all connected. Cinema!Which is reflected in other reviews, that they were really hoping this movie would answer some of the questions of what is going on in the "Cloververse." Just what is that big monster?

To do that, you first need to reverse-engineer the film to understand why The God Particle was made in the first place. Like why, at some point, did multiple people think this was a great idea for a movie?

If you actively ignore the extremely poor storytelling and exposition, God Particle actually has a very good concept for a horror movie:

The idea is that there are two parallel universes - the peace universe and the war universe. In the war universe, the space station gets sabotaged and crashes into the ocean, where the survivors are now in a fierce battle for survival.

Because of the experiment, the two universes cross over at random points - and the people from the peace universe naturally experience these crossovers as eruptions of nightmare imagery.

The most obvious example of this is when the airlock suddenly gets flooded with a ton of water - from the ocean. Air from the peace universe is being switched with water from the bad universe, and vice-versa. The Russian guy’s eye is going weird because half of his brain has been exchanged with the brain of his war-universe counterpart.

So basically there’s this entire parallel storyline where the offscreen people of the war universe figure out what’s going on, and start sending messages to the peace universe. The disembodied arm is actually connected to the Italian on the other side - so people in the war universe are basically watching their Italian crawl around on the floor while a disembodied arm floats around the room, flipping them off. The war people use this knowledge to send things like the compass through - they obviously discovered, from the worm incident, that the Russian’s stomach is the location of one of the portals. (As for how the war universe’s Russian guy ended up swallowing a ton of worms, I guess that’s left to the imagination.)

Basically everything not directly related to this narrative was added to promote the Cloverfield franchise. And it seems obvious that a lot of stuff was cut out to make it fit.

The charitable take is that the shitty ending is a probably-unintentional reference to Watchmen.

After the opening scene badly establishes the rise of nationalistic tensions and the threat of nuclear war breaking out, the utopian end-of history conclusion is accompanied by the promise/threat of a new, inhuman terrorist enemy against which we can unite. Hence the specific image of Clover - the 9/11 Kaiju par excellence.