What I knew of it (and what you probably knew) is that it shows a tragic sex crime through multiple perspectives, revealing the difference in how it looked to different people involved. I assumed it would provide expiation for the assailant, showing how they thought what they did was fine.

Turns out I was pretty wrong about that. Spoilers below the cut.

The most annoying thing about "bad" movies is how much professional reviews fail to pay attention to what is actually going on and talk about it. Turns out this is the problem for classic movies as well. Once I had finished watching this, I wanted to read analysis, so I turned to web searches and famous reviewers. For instance:

https://deepfocusreview.com/definitives/rashomon/

After three testimonies and three incompatible versions of the same story are relayed to the peasant by the priest and woodcutter, there’s yet another hint of doubt. The woodcutter admits his own court testimony was false, and that he witnessed the entire scene. He claims to have seen the bandit pleading with the woman to run away with him after the rape. In the woodcutter’s version, the wife responds with indecision, and then demands that the two men duel for her hand. Reluctantly, the men duel and the samurai is killed, but the wife and bandit each run their separate ways in terror. At the Kyoto gate, none of the men can grasp what any of it means; however, the woodcutter’s admitted presence at the scene brings into question whether or not he stole the dagger from the samurai’s body, perhaps to sell it for a hefty profit. The peasant, content that no meaning exists in such anecdotal contradictions, pessimistically resolves “Don’t worry about it—it isn’t as though men were reasonable.” All at once, the three men at the gate hear the cry of a baby. The amoral peasant begins to take the child’s clothes to sell for food, but the priest and woodcutter are appalled by this. The priest, already so confused and disenchanted by the testimonies, cannot respond, but the woodcutter intervenes. He takes the child into his arms and, just as the rain stops and Sun breaks through the clouds, the woodcutter begins to return home and vows to protect the child.

And yet, because none of the recountings can be reconciled, not even the woodcutter’s testimony, Rashomon becomes a story of unreliable narrators from whom no truth can be determined. Some form of hope exists at the film’s conclusion, but the degree to which we can believe the woodcutter depends largely on the viewer. More than one of the testimonies, if not all, including the woodcutters, must be false. They cannot all be true given the opposing possibilities of the samurai’s death, the missing dagger, and a number of other loose ends.https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-rashomon-1950

Kurosawa is correct that the screenplay is comprehensible as exactly what it is: Four testimonies that do not match. It is human nature to listen to witnesses and decide who is telling the truth, but the first words of the screenplay, spoken by the woodcutter, are "I just don't understand." His problem is that he has heard the same events described by all three participants in three different ways--and all three claim to be the killer.

From these many paragraphs of analysis you will get... that there were four different versions of events told, and none of them was "true" and thus we learn a great lesson about how truth is impossible but there's a baby at the end so there is still hope.

This is nothing. This anti-analysis tells nothing of the different stories, and how they related, and why they disagreed with each other, and why each person would offer the particular version they did.

(Disclaimers: said reviews do offer some cinematographic commentary on the use of light, and what the audience "represents." This is at least something, but these datapoints are not used in the construction of any argument.

There are also probably better analyses out there. Not on the first page of google, or perhaps even locked away in books. For instance I'd love to read the booklet that Kurosawa wrote that was included with the Criterion edition. All I can say is a) this is what people find first doing research into the movie, and b) if you have better reviews, send them to me.)

So. What is this goddamn movie about?

Identity.

Let's go back to the cliche of the above reviews, which is that all four versions of events - one from each participant, and one from a bystander secretly watching - are lies and shaded by the interests of the teller. This relativism/nihilism is all very sophisticated, but not really supported by the film.

Our starting point should be that the bystander is the most objective viewer. Each person is trying to defend their own position in some way... and he isn't. He's last to tell. We should not give 100% blind faith to the "objective viewpoint", but come on, we should at least start with the idea that his story is the most accurate.

(This is supported by the text: in that the pearl-decorated dagger that is a much discussed fetish object, is a metaphor for the truth. Each story is true in as much as it holds on to the dagger.

- The crazy-evil Bandit just forgot it altogether.

- The wailing Wife blacked out and missed what happened to it.

- The Samurai had it taken from him when he was dead.

As for the witness-woodcutter... we do not see him with the valuable dagger either, but when accused of taking it and selling it for gold, he gives silent admission to the fact. He is closer to the truth than anyone else.)

But look at us, so far we have just discussed this so abstractly. "Truth is like a three edged sword" or some shit, without ever having discussed what was in these different versions and why do we trust one over the others. It is in the Real of the details that we can understand this story, the details and what they say about identity.

***

Rashomon is in fact a fantastic investigation of the gender trinary that Balioc discusses:

The game requires exactly three players. This is because there are three roles in the story: Hero, Maiden, and Monster.

In the broadest sense, there is only one way the story can play out. The Monster, who is transgressive, lays a claim on the Maiden, who is desirable and pure. The Hero contests this claim, defeats the Monster, and saves the Maiden. Everyone knows that this is how things are going to go. Everyone accepts it. Why else would you become a Hero, a Maiden, or a Monster in the first place?

But this primordial story-skeleton has room for lots of variation. And it is within those variations that the conflicting interests of the participants play out.

Link, Zelda, Gannon. Othello, Desdemona, Iago. Aladdin, Jasmin, Jafar. Prince Charming, Sleeping Beauty, Aurora -- but when subverted: Gaston, Belle, the Beast. Mario, Princess Peach, Bowser. The list goes on and on, with there being as many triptychs as there are stories, at least in certain genres.

We get an attack in the forest, where the bandit ties up the samurai, and has his way with his trophy wife in front of him. (The wife fought valiantly with her pearl dagger, but eventually lost, and in the last minutes gave in to his seduction.) These details, while relayed by the bandit, are not contradicted by anyone else.

After that the samurai was killed. By who and why is what the different people disagree over. And so we get the story from the monster, the maiden, and then the hero (told diagetically through a medium who greatly influences the delivery.)

As Ebert wonders "all three claim to be the killer." We could imagine people trying to excuse themselves or cast blame on others, but why would each participant take blame for the murder?

To support their social identity in the gender trinary, of course.

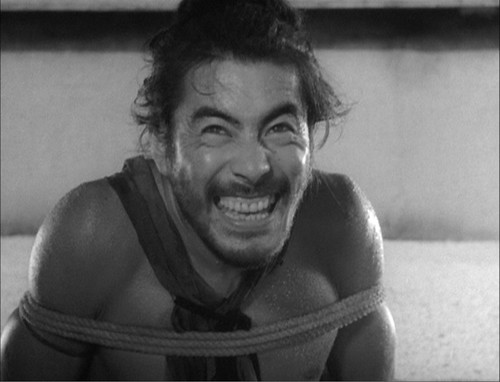

The bandit reveals this in his first words. He is not trying to plead his innocence. He is a monster, who cackles and rambles madly about his depraved acts. He will probably be punished or killed, and yet, only be embracing this mask of capital-E-vil, can he be granted any dignity from his lonely, degraded existence. Everything he says is to sell the image of him as the fiercest bandit and ugliest monster in Japan. The tell of course is when at the end of his story he says he dueled the samurai for the wife's honor:

I wanted to kill him honestly, since I had to kill him. And he fought really well. We crossed swords over twenty-three times. Think of that! No one had ever crossed over twenty with me before. Then I killed him.

He's been allowed to add honor and excitement to his story, with no one being skeptical of him, because he gives the judge and audience what they want: a villain to blame.

The wife's story is less gleeful, but really follows a similar pattern. In the eyes of her sexist society - that fetishizes her angelic beauty, sees her sexual purity as an object to be preserved, and when that is lost then sees her as a ruined and disgraced beast - she has suffered the ultimate tragedy a woman can. There is no longer a respectable place for her.

And yet that ruin is itself an identity. She can still have a dignity of sorts if she embraces this story of tragic victim. Everyone nods at how her cruel husband now hates her, her wailing grief, and her blackout as she drove her dagger into her husband in shameful rage. Of course she is obligated to try to commit suicide, which she tries and fails, and is utterly miserable. But she also has a concrete role in society with all this, and her telling of her story builds up that particular mask for her.

The samurai husband gets to tell his story too, but it's really told by an extremely dramatic spirit medium. In this way, the "hero's tale" is the one most designed to satisfy society overall. He had been defeated, his greatest treasure stolen from him, and now she wants him dead to hide her disgrace, so he offs himself seeing no reason to live (after declaring her worse than the bandit.) The hero at this juncture can't pretend that he "won", so he spins a tale that he quit of his own accord. (There's not much about it to say. Without the medium's delivery, by this point the story would be getting rather boring.)

[It should be noted at this point that most modern takes on this subjective style of story-telling, like a How I Met Your Mother episode about a catastrophic party, keep the objective facts like "what words were said" the same, but use tone and delivery and atmosphere to change the meaning of those facts. The original 1950 breakthrough was not that advanced, and the facts of the matter really do contradict each other. Someone is lying, not just using rose-tinted goggles.]

These different narratives about identity might seem subtle or silly, but when thrown into relief by the woodcutter's account, we can see the desperation in their meaning.

The woodcutter isn't coolly objective - rather he is panicked and anxious, for what he has seen is both absurdly pathetic and grossly horrific. It's completely different from the symbolic reality we tell ourselves, which is why he is so unable to tell it calmly, but also he can't keep it hidden. He isn't objective, so much as what he saw was terrifyingly real.

None of the stories told were like what the participants actually did.

The wife wails her grief. The bandit obsequiously offers to duel for her. The samurai grimly says such a ruined woman isn't worth risking his life over. The bandit agrees, but it's not her fault as "woman are weak."

This is the moment when things go batshit off the rails crazy, and the best part of the movie. The ruined object transitions from crying to screaming madness, declaring that the MEN are weak, who are blaming her despoilment to cover for their real fear of violence. She howls and taunts at them, shaming the two men into dueling for her. It is a fantastic performance. And the two men are pants-wettingly scared of violence. We're treated to an enlongated slapstick scene of them scrambling away from each other, tepidly keeping distance, falling about in the slippery leaves, and all in all acting like greenfeet who have never had to duel fairly and for their life. It's both maudlin and hilarious. Finally the samurai loses his sword and falls down, and begs not to die as the bandit slaughters him. Both the monster and maiden are traumatized at actual bloodshed, and she runs off with the bandit mewingly chasing after her.

It's amazing story-telling that gives complete lie to the "cinema" of the previous three stories. No one is dignified, and no one properly fits the social "role" that Japanese society expects of them. The woodcutter saw this truth, and can not reconcile it both with what he had been raised to believe, nor with what the participants testified to. He is not the objective observer, but rather the survivor of a traumatic encounter with the Real. Like the pearl dagger, he grasps truth briefly, but sells it away because it is too painful to keep.

***

I meant to add that there are really five versions of the story told. Woodcutter tells his tale to start everything off - that he saw nothing but found the Samurai. This, like the middle three, is revealed to be a lie by the final Woodcutter story, based on his desire to stay invisible and out of trouble. So in the final, ridiculous version, four people have their ideal social role contradicted.

***

The movie that all the critics think they are watching is Capturing the Friedmans, which is legit about “the unknowability of truth” when multiple different valances of accountings settle nothing about the reality of what has happened. I agree that Rashomon is about identity as a personal narrative that actions/desires/facts need to be “made to fit.” Interestingly, in all 3 participant’s stories, the characters “fail” their archetypal goal but the memories are deformed not to see themselves in the best possible light, but to preserve the story itself and their role in it, since in the real version everyone does something they cannot do and still be who they need to be seen to be (most of all by themselves).

***

This is great.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting!

ReplyDelete