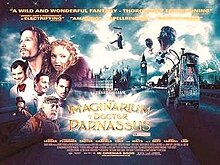

I finally saw this cult classic of Terry Gilliam and Heath Ledger's final half-performance. Like all my reviews, spoilers abound, so placing this below the cut.

Imaginarium is an old school tale.

Virtually all our mass-culture narratives based on folklore have the same structure: good guys battle bad guys for the moral future of society. These tropes are all over our movies and comic books, in Narnia and at Hogwarts, and yet they don’t exist in any folktales, myths or ancient epics. In Marvel comics, Thor has to be worthy of his hammer, and he proves his worth with moral qualities. But in ancient myth, Thor is a god with powers and motives beyond any such idea as ‘worthiness’.

In old folktales, no one fights for values. Individual stories might show the virtues of honesty or hospitality, but there’s no agreement among folktales about which actions are good or bad. When characters get their comeuppance for disobeying advice, for example, there is likely another similar story in which the protagonist survives only because he disobeys advice. Defending a consistent set of values is so central to the logic of newer plots that the stories themselves are often reshaped to create values for characters such as Thor and Loki – who in the 16th-century Icelandic Edda had personalities rather than consistent moral orientations.

Stories from an oral tradition never have anything like a modern good guy or bad guy in them, despite their reputation for being moralising. In stories such as Jack and the Beanstalk or Sleeping Beauty, just who is the good guy? Jack is the protagonist we’re meant to root for, yet he has no ethical justification for stealing the giant’s things. Does Sleeping Beauty care about goodness? Does anyone fight crime? Even tales that can be made to seem like they are about good versus evil, such as the story of Cinderella, do not hinge on so simple a moral dichotomy. In traditional oral versions, Cinderella merely needs to be beautiful to make the story work. In the Three Little Pigs, neither pigs nor wolf deploy tactics that the other side wouldn’t stoop to. It’s just a question of who gets dinner first, not good versus evil.

- https://aeon.co/essays/why-is-pop-culture-obsessed-with-battles-between-good-and-evilThere's a lot wrong with that article, but this essential historical point is correct. Just go look up descriptions of old school fairy tales like the Snow Queen and try to find a conventional narrative or morality (which is why Disney had to modify it so greatly to make it into Frozen.)

It's easy to watch Imaginarium and say "wait a minute, just who is the good guy? The doctor who bets his daughter's life and then gets drunk while he's supposed to be saving it, the slick con man who revives the crew's fortunes but also sells children's organs, the sixteen year old boy with a case of Nice Guy so bad he commits the film's closest thing to sexual assault? It's certainly not the agency-less ingenue or the devil himself." This isn't one of those things where the movie has an intended hero and I'm picking at their behavior - no character in this movie is presented as consistently sympathetic or well-intentioned.

People just do things. Some of those things are bad or good, but they do not unify in a bad or good character, nor in a film that rewards being good. It's not even like "Love, Actually" or "Seinfield" - narratives with amoral characters but who are in moral universes and so we explore what it's like "to feel like a bad person." It's just a fairy tale whose logic we never understand.

It's dream logic of course. When you know exactly where you are but not how you got there. Where everything in some absurd way makes sense going from one moment to another, but definitely doesn't follow beyond that. You're either down for this and the roller coaster of imagery and emotions it presents, or you aren't, and you'll wonder "what the hell is the characterization and plot."

The best line is uttered to a fake-amnesiac demanding "where are we?" "Geographically? Northern hemisphere. Socially? On the margins. Narratively? A ways to go."

***

It's impossible for this story not to be incredibly, self-indulgently meta. It's Terry Gilliam talking about the pain of making art. It's Heath Ledger dying and so being played by another famous rogue each time he enters a CGI wonderland. So let's engage with that.

The Devil is not at all what he appears.

He's certainly not interested in winning bets that are about the triumph of evil. He patently throws at least three bets, with increasingly pathetic excuses. He's... lonely, and bored.

He also doesn't stand for evil. One of the most memorable Fateful Moral Choices offered to some characters in the film is "join the police where you can practice sexy violence and it's legal" versus "go home to the comforting embrace of mother and the farm"... and the latter one is the Devil's path.

In fact, if we look at the different choices offered to the Imaginarium suplicates (ibid, Heaven's Steep Steps vs a dive bar, a one night stand motel vs a famous death) and the initial conflict between Parnassus and the Devil, the difference is clear. Parnassus stands for stories, myths, hard sacrifices and glorious dreams, becoming something greater than what you are. The Devil is nihilism, Tsathoggua, laziness, being small, material comforts. He is the denial that stories have any value, or that people will ever choose greatness.

Which gives us two interesting conclusions: one, nihilism is right, and can always trivially win, but engages with Hastur because he's bored and has nothing else to do.

Two, this is why Parnassus's daughter, who fantasizes about home furnishing magazines and leaving the circus behind, very forcefully chooses the Devil's door.

***

Edit: Meant to add, that just because Parnassus represents "mythic potential" does not mean he's "good". He has the major flaw that he just doesn't care about other people. The movie starts off with presenting the ricketty stage unfurling in front a bunch of apathetic drunks, which at first makes us feel bad for the artists for being unappreciated by a banal world... but it quickly becomes clear they aren't even trying. Their failure to connect with the audience is as much their doing as modernity's. (This is highlighted by the imagery of the great doctor just sitting their insensate on the stage. He is the most navel-gazing auteur.)

Tony exists at the opposite end of this spectrum, using storytelling as solely a mask for connecting with others. He goes out and finds them appreciative audiences, lies to them and seduces them, and changes the company's presentation to appeal to others. This all matches with the sort of con-man life he had before, and in the Imaginarium himself he literally changes faces to be what others want.

The movie isn't saying one of these is better than the others. It's not even saying "you want a happy balance between self-indulgent storytelling and seducing the audience." It's just presenting "these are ways people use stories, sometimes beneficial but also sometimes gross."

To be fair, the Snow Queen isn't an old-school fairy tale. It's a rather recent story by Hans Christian Anderson.

ReplyDeleteBut if you ask me, Anderson's corpus is rather abnormal, even for the time. So many of his stories are basically "people did interesting things, and then they died."

Anderson aside, I disagree with this idea that older tales lacked morals. They may have lacked morals as we currently conceive of them, but there is no way that the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon didn't reflect Greek ideas about moral behavior.

Even trickster tales, which certainly seem amoral, probably reflect the moral goods of "being clever even though you're smaller and weaker than others." After all, Bre'er Fox would certainly eat Bre'er Rabbit if he could catch him.

Now, I'll grant that many of the Greek myths are relatively amoral. But then, the universe itself is capricious, and people seek to understand that.

But is Jack and the Beanstalk immoral? The giant is a cannibal. Jack is a starving peasant; the giant lives like a king. The giant isn't even human--he's a monster. I suspect the audience would have taken it for granted that the morally right thing to do is to kill alien cannibals and give their wealth to starving peasants.

Cinderella is certainly a moralizing tale. Cinderella works hard without complaining, despite adversity. She is kind to others (often the gift of the slippers is due to some kindness she has done.) And while everything looks hopeless at first, in the end, the wicked are punished.

Sleeping Beauty seems to me like a story about hope for the dead, in an era where things like sickness and comas weren't very well understood. It isn't exactly moral--but it does note that sometimes bad things happen to good people, with an expectation that in the end, they will be put to right.

Crime is punished in many fairy tales--evil stepmothers are often punished quite gruesomely.

The moral of the Three Little Pigs isn't about the wolf (who is, of course, a glutton,) but about the value of working hard and not being lazy. The lazy pigs get eaten. The hard-working pig lives. You tell children about the Three Little Pigs not to explain why wolves are bad (children already know why wolves are bad). You tell it to them to explain why they should work hard.

Going further back, the Epic of Gilgamesh contains morals. How can we say that Gilgamesh was a cruel king and Enkidu a kind man without some conception of "cruelty" and "kindness"? Yet through Enkidu's friendship, Gilgamesh became a good man and king to his people. The Bible, whether one likes it or not, contains a great many stories with moral points.

Thor and Loki, I grant, I don't know much about. Perhaps they are indeed immoral. But overall, the idea that older stories lacked morals seems quite wrong. Perhaps they lacked our morals. But people have been trying to explain moral behavior to their children since time immemorial, and that is bound to be reflected in at least some of their stories.